Before we begin to answer the question of how Nepalis enter the U.S., we must first have a basic understanding of how the U.S. immigration system functions.

Before 1965, the U.S. had a national origins system, meaning that nations received different quotas of how many people from that country were allowed to immigrate to the U.S. However, in 1965, this system was abolished, and a new law called the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was enacted. Under this new law, family reunification and recruiting skilled professionals to the U.S. were prioritized. 75% of visas were set aside for the relatives of those already in the U.S., with most remaining visas being allocated for people with certain job skills. This 1965 law included a quota for refugees, but the Refugee Act of 1980 would later separate refugee admissions from the overall quota system.

Above: the signing of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

Though there have been new immigration laws implemented in the time since — such as DACA and DAPA — the 1965 law is still in place today and is what defines much of our immigration system. Today, there are several different types of immigrants: immigrants with an immediate family member living in the U.S., immigrants who are married to or engaged to a U.S. citizen, and different categories of workers, which we will explain later. This system of immigration favors family reunification, which is not helpful for many Nepali immigrants — due to the relatively late start of Nepali immigration to the U.S., there are not many Nepalese people with family in the U.S. who can sponsor them through this system.

Above: an example of the paperwork that Nepali immigrants to the U.S. have to fill out to enter the country.

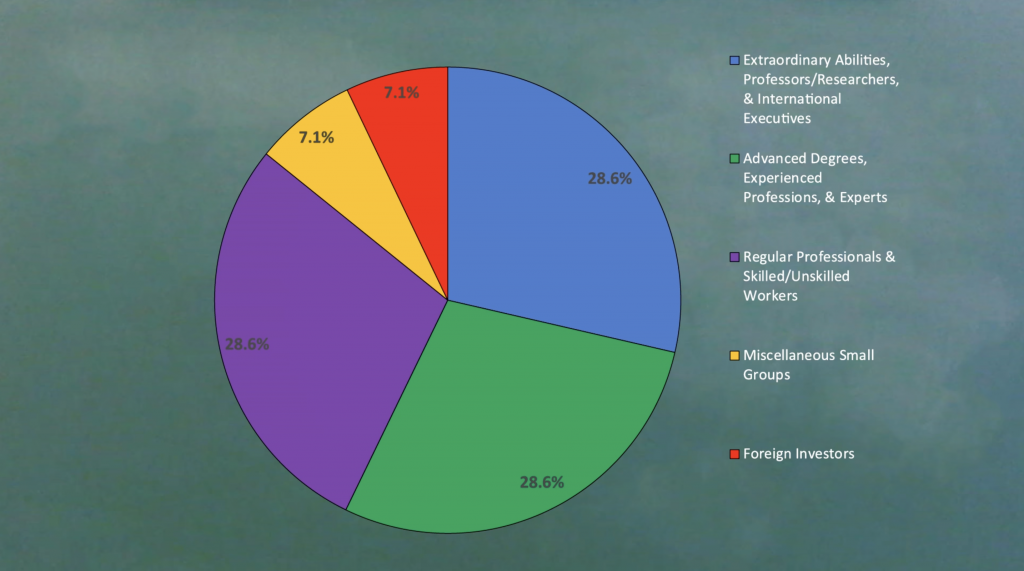

In the category of workers, there are five distinct groups, each of which is allocated a specific number of visas. First, there are workers of “extraordinary ability” in their field — these people, unlike other workers, do not need a job offer before they begin the process of immigrating to the United States. Second, there are workers with “advanced degrees.” Third, there are “unskilled, skilled, and professional workers.” Unskilled work is defined as a job that requires less than two years of experience or training. Skilled work is defined as a job which requires more than two years of experience or training. Professional work is defined as a job that requires a college degree. The fourth group of workers consists of a bunch of special groups, such as religious ministers and former employees of the U.S. government abroad. The last group is people who have invested $1 million into the U.S. economy and have created at least 10 jobs for American workers. Here is a breakdown of how many visas are allocated to workers in each category:

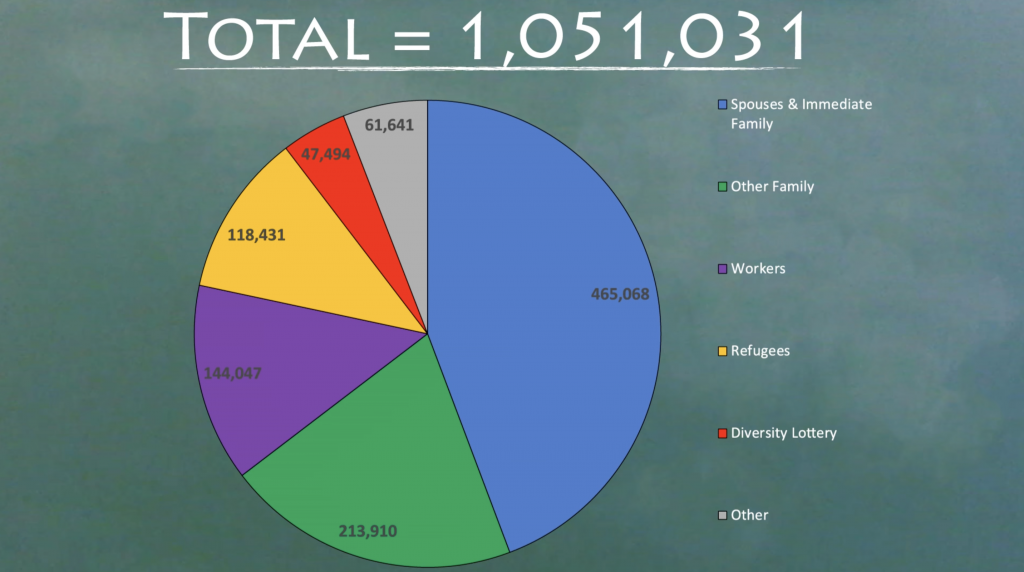

In addition to the limit placed on the number of visas available for people in these categories, there’s also a limit to how many people can come from a particular country. So even if you’re a professional with an advanced degree, if your country has already sent the maximum number of immigrants it can send, it’s unlikely you will be able to immigrate to the United States. Here is a breakdown of how many visas were allocated to each category of immigrant in 2015:

You may have noticed another category in this pie chart called the Diversity Lottery. Every year, a special lottery takes place where 50,000 visa applicants are randomly selected from countries that have sent less than 50,000 immigrants to the U.S. in the last five years. This is called the Diversity Immigrant Visa Program, otherwise known as the Green Card Lottery. In order to qualify for this lottery, you need 2 years of work experience, a high school education, and a skilled profession.

Each year, over a million Nepalis enter the Diversity Visa Lottery. Though winning the lottery is a dream of many who wish to immigrate to the U.S., it’s still difficult to leave behind one’s entire community. Here’s how one Nepali describes the feeling of winning the Diversity Visa Lottery:

When we won the lottery, we were both happy and sad. It was a hard decision to make. We were socially and economically well established in Nepal. I used to work for Nepal Bank and my husband was a well-known attorney. My husband owns a law firm and he has shares in hotels. Both of us were very much engaged in social organizations and social work in our community. My husband and I wouldn’t have wanted to come here if it were not for our children. We didn’t want to start from scratch in America. But for our children, for their education, and for their future, we risked everything and came to America. If our political situation were stable and good in Nepal, we would not have applied for the diversity visa lottery.

Above: a graphic congratulating Nepalis who had won the Diversity Visa Lottery.

Before the implementation of the Diversity Visa Lottery, most Nepali immigrants had to be highly educated and technically trained in order to meet the worker category requirements for immigrants. Today, less educated Nepalese have been able to come because of this new lottery system. However, it’s important to acknowledge that the average Nepali immigrant to the U.S. still has to be somewhat socioeconomically advantaged, as socioeconomically disadvantaged groups do not have the money required to pay for the pre-departure agreement.

There are a few other ways that Nepalis immigrate to the U.S. Because of the Nepalese Civil War and the 2015 earthquake, some Nepalese people have received Temporary Protected Status, which allows them to stay in the U.S. because of their extraordinary circumstances. Approximately 9,000 Nepali immigrants came to the U.S. through the Temporary Protected Status program after the 2015 earthquake. Additionally, some Nepalis are protected by DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals). There are also 10,000 to 15,000 Nepali students who come to different U.S. universities to pursue higher education each year. The number of Nepalis in higher education is rapidly increasing — Nepali students were 0.9% of all foreign students during the 2013-2014 school year, a remarkable number because of how small the nation is.

Above: Nepali students studying in the U.S.

Additionally, around 1,000 Nepalis each year try to enter the U.S. illegally through the Southern border with Mexico. In order to do this, they have to transit through as many as 13 countries to get there.

As this brief summary shows, Nepali immigrants are a diverse group, coming to the U.S. for a variety of distinct reasons. Overall, migration has become an important part of contemporary Nepalese identity. Since 2000, the amount of Nepali people laboring abroad has increased tenfold. The country’s population is 30 million, 4 million of whom — 15% of the population — have migrated abroad for work. Approximately 1,500 people leave Nepal each day, with remittances accounting for ⅓ of the country’s GDP.