When you hear the word “Nepal,” what do you think of? Perhaps you imagine Mount Everest and the towering peaks of the Himalayas that so many hikers try to brave each year. Or perhaps you think of the Buddha, as he was born in Lumbini. Regardless of what comes to mind, you probably think of a country that’s far away, on a different continent, across the entire Atlantic or Pacific Ocean, depending on what side of the country you’re on. But did you know there are actually thousands of Nepalis living in the United States today?

This webpage will serve as an introduction to the history of Nepali migration to the United States and the vibrant Nepali American community that exists here today.

By the Numbers

As of 2019, there were 198,000 Nepalis living in the United States. Though this may sound like a large number, compared to other South Asian immigrant communities in the United States, this is actually relatively small. This smaller U.S. population is due to the fact that other South Asian countries, such as India and Pakistan, have much longer histories of immigrating to the U.S., whereas Nepali migration to the United States only began relatively recently.

The top U.S. metropolitan areas for Nepalis today are Dallas, New York, Washington, San Francisco, Baltimore, Boston, Atlanta, Pittsburgh, Akron, and Chicago.

The top 10 states with the highest Nepali populations are Texas, New York, California, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Colorado.

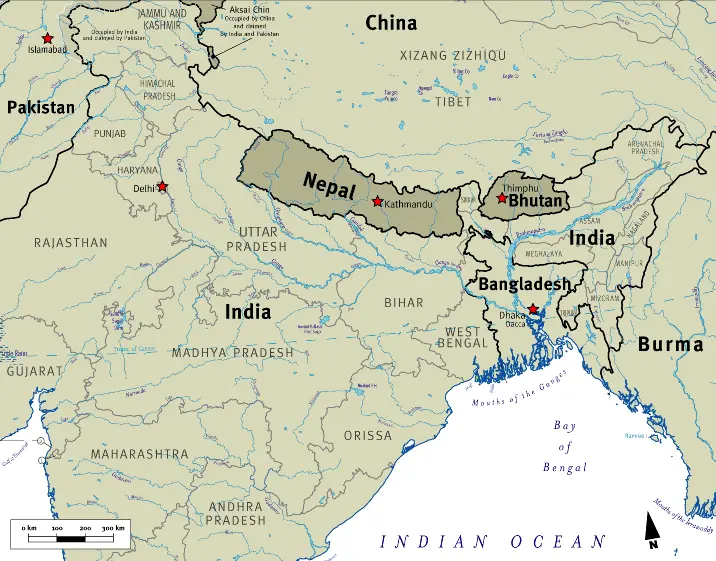

Though the amount of Nepali immigrants in the United States is relatively small, it’s a diverse group, with a variety of Nepali ethnic and geographic backgrounds represented. The predominant ethnic subgroup among Nepali immigrants is the Bahun Chetris, who are of Indo-Aryan Hindu origins. Their ancestors are originally from the middle, hilly region of Nepal. The Newar people — the ethnic group indigenous to the Kathmandu valley — are also a predominant ethnic subgroup among Nepali immigrants to the U.S. Here’s a map of Nepal for reference:

Nepali-speaking Bhutanese, known as Lhotshampas, also make up a large number of Nepali immigrants to the U.S. Bhutanese Nepali speakers are Bhutanese citizens of Nepali origin, who fled Bhutan as refugees when the country began an ethnic cleansing of minority groups in the late 1980s. According to the UNHCR’s 2015 report, there are 84,000 Bhutanese Nepalese living in the U.S. today. Here’s where Bhutan and Nepal are in relation to each other:

Because a diversity of ethnic groups are represented among Nepali immigrants, a diversity of languages is represented as well. For example, though the national language of Nepal is officially Nepali, many Newar immigrants to the U.S. speak Newari. Other languages spoken in Nepalese American communities include Sherpa, Tamang, and Gurung, among many others. However, among Nepali immigrants in the U.S., most use Nepalese as their main language of communication within their communities.

Here are some links to clips of Nepalese people speaking the different languages of Nepal:

- Nepali – national language of Nepal, the most widely spoken in the country, Indo-Aryan in origin

- Newari – language spoken by the indigenous people of the Kathmandu valley, Sino-Tibetan in origin

- Sherpa – language spoken by the Sherpa ethnic group, Tibetan in origin, also spoken in Northern parts of India

- Tamang – language spoken in Nepal, Sikkim, West Bengal, and North-Eastern India, Sino-Tibetan in origin

- Gurung – language spoken by the Gurung ethnic group, Sino-Tibetan in origin

Above: the Nepalese alphabet being written out. Click here to learn more about the Nepali alphabet!

As of 2019, the Nepali American median household income was $55,000 a year, compared to the $85,800 median of all Asians in the U.S. and the $68,000 median of all Americans. 17% of Nepali Americans are at poverty or lower, compared to 10% of all Asians in the U.S. and 11% of all Americans.

Because the Nepali population in the U.S. is still relatively small, there aren’t many distinct Nepali enclaves in U.S. cities, such as Chinatowns in the case of Chinese immigrants or Little Koreas in the case of Korean immigrants. However, in Jackson Heights, Queens, there is an area that some people call “mini-Nepal,” which has Nepali restaurants, grocery stores, and more. Click on the images below to learn more about “mini-Nepal!”

The First Nepali Immigrant

It’s very difficult to pinpoint the first Nepali immigrant to the U.S. During the majority of U.S. history, Nepali immigrants were classified simply as “other Asian.” Between 1881 and 1890, 1,910 people classified as “other Asians” immigrated to the U.S. Though perhaps some of these “other Asians” were Nepalis, it’s impossible to say.

However, what we can say is that it is very unlikely that any of these “other Asians” were Nepalese because the Anglo-Nepal Treaty of 1816 closed Nepal to all foreigners except the British, and forbade Nepalese from legally emigrating anywhere except India. During this period, there was also some Nepali migration to Britain and its colonies, as Nepali troops were supplied to the British army and police forces as part of this treaty. This led to many Nepali men — called Gurkha soldiers — ending up in Britain and its colonies.

Above: Gurkha soldiers during World War II.

Additionally, the lack of a diplomatic relationship between Nepal and the U.S. until 1947 and the country’s limited access to Western material culture and languages also make it very unlikely that Nepalis were included in this first group of “other Asians” who immigrated to the United States.

In order to understand Nepali immigration to the U.S., it is important to realize that Nepal’s social, political, and economic ties with the outside world only began in the early 1950s. In 1951, the autocratic Rana regime was overthrown, increasing Nepal’s contact with the outside world and allowing more Nepalis to immigrate to different countries across the world, including the United States.

However, after the royal coup of 1960, parliamentary democracy collapsed, making Nepali immigration very difficult once again. When democracy was finally restored to Nepal in 1990, the number of Nepali immigrants to the U.S. increased significantly. It also helped that in the 1990s, the U.S. government implemented a new immigration lottery system that greatly benefited Nepali immigrants, a system that we will explain in depth later.

Though we cannot know precisely when the first Nepali immigrated to the United States, what we do know is that the first Nepalese person obtained permanent residency in the United States in 1952. We also know that in 1975, Nepalis were classified as a separate group of immigrants for the first time in U.S. history. That year, 56 Nepalese people immigrated to the United States. Post-1975, the number of Nepali immigrants to the U.S. remained below 100 per year until 1996, when the implementation of the Diversity Visa Program caused Nepalis immigration to the U.S. to skyrocket.

Above: Nepalis in Kathmandu at the passport office. The passport office has seen a record amount of people after the U.S. announced in 2019 that a passport was required to enter the Diversity Visa Lottery.

Another reason why there was such an increase in the number of Nepali immigrants to the U.S. in the late 90s and early 2000s was because of the Nepalese Civil War. Lasting from 1996 to 2006, this violent conflict drove many people from their homes, especially in the west of Nepal. Thus, because of this conflict, more Nepalis started to view immigrating to the U.S. as an option.

The United States and its so-called “War on Drugs” is also partially responsible for the increase in Nepali immigrants in the latter half of the twentieth century. As a part of its international war on drugs, the United States targeted Nepal, which was known as a place where hippies went and smoked marijuana. In 1972, U.S. vice president Spiro Agnew visited Nepal and just months later Nepal enacted its first anti-drug laws. These laws were harmful to many in the western mountainous region of Nepal, who relied on cultivating and selling marijuana for their livelihoods. Thus, many in this region were suddenly impoverished and these laws led to a collapse of the local economy, leaving many wondering if they could seek a better life for themselves in the U.S.

Though Nepali immigration to the U.S. is a relatively recent phenomenon, Nepalis are one of the fastest-growing immigrant communities in major U.S. cities.

How Do Nepalis Enter the U.S.?

Before we begin to answer the question of how Nepalis enter the U.S., we must first have a basic understanding of how the U.S. immigration system functions.

Before 1965, the U.S. had a national origins system, meaning that nations received different quotas of how many people from that country were allowed to immigrate to the U.S. However, in 1965, this system was abolished, and a new law called the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was enacted. Under this new law, family reunification and recruiting skilled professionals to the U.S. were prioritized. 75% of visas were set aside for the relatives of those already in the U.S., with most remaining visas being allocated for people with certain job skills. This 1965 law included a quota for refugees, but the Refugee Act of 1980 would later separate refugee admissions from the overall quota system.

Above: the signing of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

Though there have been new immigration laws implemented in the time since — such as DACA and DAPA — the 1965 law is still in place today and is what defines much of our immigration system. Today, there are several different types of immigrants: immigrants with an immediate family member living in the U.S., immigrants who are married to or engaged to a U.S. citizen, and different categories of workers, which we will explain later. This system of immigration favors family reunification, which is not helpful for many Nepali immigrants — due to the relatively late start of Nepali immigration to the U.S., there are not many Nepalese people with family in the U.S. who can sponsor them through this system.

Above: an example of the paperwork that Nepali immigrants to the U.S. have to fill out to enter the country.

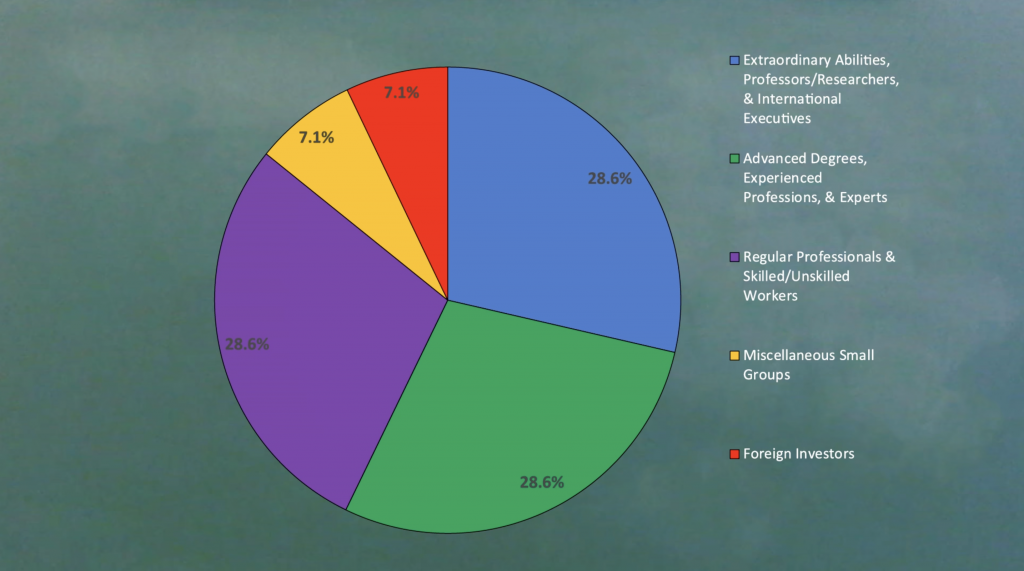

In the category of workers, there are five distinct groups, each of which is allocated a specific number of visas. First, there are workers of “extraordinary ability” in their field — these people, unlike other workers, do not need a job offer before they begin the process of immigrating to the United States. Second, there are workers with “advanced degrees.” Third, there are “unskilled, skilled, and professional workers.” Unskilled work is defined as a job that requires less than two years of experience or training. Skilled work is defined as a job which requires more than two years of experience or training. Professional work is defined as a job that requires a college degree. The fourth group of workers consists of a bunch of special groups, such as religious ministers and former employees of the U.S. government abroad. The last group is people who have invested $1 million into the U.S. economy and have created at least 10 jobs for American workers. Here is a breakdown of how many visas are allocated to workers in each category:

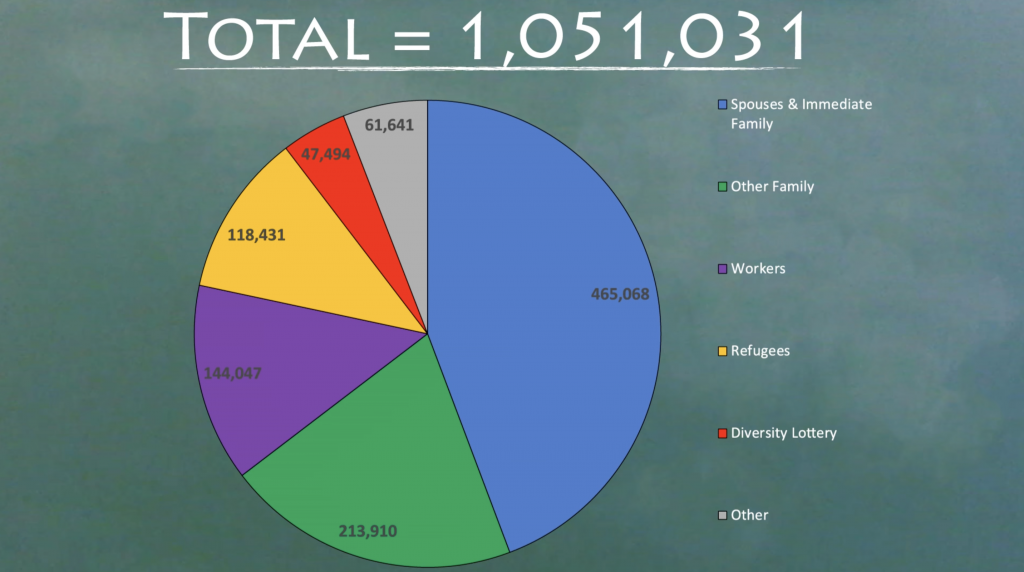

In addition to the limit placed on the number of visas available for people in these categories, there’s also a limit to how many people can come from a particular country. So even if you’re a professional with an advanced degree, if your country has already sent the maximum number of immigrants it can send, it’s unlikely you will be able to immigrate to the United States. Here is a breakdown of how many visas were allocated to each category of immigrant in 2015:

You may have noticed another category in this pie chart called the Diversity Lottery. Every year, a special lottery takes place where 50,000 visa applicants are randomly selected from countries that have sent less than 50,000 immigrants to the U.S. in the last five years. This is called the Diversity Immigrant Visa Program, otherwise known as the Green Card Lottery. In order to qualify for this lottery, you need 2 years of work experience, a high school education, and a skilled profession.

Each year, over a million Nepalis enter the Diversity Visa Lottery. Though winning the lottery is a dream of many who wish to immigrate to the U.S., it’s still difficult to leave behind one’s entire community. Here’s how one Nepali describes the feeling of winning the Diversity Visa Lottery:

When we won the lottery, we were both happy and sad. It was a hard decision to make. We were socially and economically well established in Nepal. I used to work for Nepal Bank and my husband was a well-known attorney. My husband owns a law firm and he has shares in hotels. Both of us were very much engaged in social organizations and social work in our community. My husband and I wouldn’t have wanted to come here if it were not for our children. We didn’t want to start from scratch in America. But for our children, for their education, and for their future, we risked everything and came to America. If our political situation were stable and good in Nepal, we would not have applied for the diversity visa lottery.

Above: a graphic congratulating Nepalis who had won the Diversity Visa Lottery.

Before the implementation of the Diversity Visa Lottery, most Nepali immigrants had to be highly educated and technically trained in order to meet the worker category requirements for immigrants. Today, less educated Nepalese have been able to come because of this new lottery system. However, it’s important to acknowledge that the average Nepali immigrant to the U.S. still has to be somewhat socioeconomically advantaged, as socioeconomically disadvantaged groups do not have the money required to pay for the pre-departure agreement.

There are a few other ways that Nepalis immigrate to the U.S. Because of the Nepalese Civil War and the 2015 earthquake, some Nepalese people have received Temporary Protected Status, which allows them to stay in the U.S. because of their extraordinary circumstances. Approximately 9,000 Nepali immigrants came to the U.S. through the Temporary Protected Status program after the 2015 earthquake. Additionally, some Nepalis are protected by DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals). There are also 10,000 to 15,000 Nepali students who come to different U.S. universities to pursue higher education each year. The number of Nepalis in higher education is rapidly increasing — Nepali students were 0.9% of all foreign students during the 2013-2014 school year, a remarkable number because of how small the nation is.

Above: Nepali students studying in the U.S.

Additionally, around 1,000 Nepalis each year try to enter the U.S. illegally through the Southern border with Mexico. In order to do this, they have to transit through as many as 13 countries to get there.

As this brief summary shows, Nepali immigrants are a diverse group, coming to the U.S. for a variety of distinct reasons. Overall, migration has become an important part of contemporary Nepalese identity. Since 2000, the amount of Nepali people laboring abroad has increased tenfold. The country’s population is 30 million, 4 million of whom — 15% of the population — have migrated abroad for work. Approximately 1,500 people leave Nepal each day, with remittances accounting for ⅓ of the country’s GDP.

Patterns in Migration Today

Socioeconomic background is often the biggest predictor of where Nepali people migrate. People with lower socioeconomic backgrounds tend to migrate to India and Gulf nations, such as Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Those with higher socioeconomic statuses tend to migrate to the U.S., Canada, Australia, and European countries.

Additionally, certain regions in Nepal experience exceptionally high rates of migration. For example, the Mustang district in Northern Nepal has one of the highest rates of depopulation in the country. It is estimated that ¼ of the culturally Tibetan people from the Mustang District live in New York City.

Above: a map showing where the Mustang district in Nepal is located.

Additionally, women make up 68% of Nepali international labor migrants today. This is a recent pattern, as in the early 1990s, it was unusual for Nepali women to migrate to the United States without their families. In the early 1990s, the majority of Nepali women who migrated to the U.S. came with their husbands who were attending graduate school, in order to take care of children and perform care work for extra pay.

However, this began to change in the late 1990s, as educated women began to migrate from Nepal to the U.S. to take advantage of the wage differentials between the U.S. and Nepal. These women contribute not only to their families but also to their villages and international charitable organizations. They send money regularly to support social organizations and non-family members, which is a new phenomenon, as in the past, labor migrants focused on supporting their direct families and communities. Examples of the social organizations these women support include religious institutions, nonreligious NGOs, and sponsoring orphaned/underprivileged children.

These women mainly immigrate to Boston and New York City, mostly by themselves. The majority are educated professionals or semi-professionals in Nepal, who now work in low-paid service or as care workers. Their jobs range from childcare providers, restaurant workers, house cleaners, and domestics, with the vast majority working for South Asian Indian employers. Here’s how these women describe their experiences:

I learned quickly that the only way to get a good job here was to get a degree from here. That wasn’t so practical for me. So the only work available for me was house cleaning, which doesn’t require any degree or formal training.

I came to America to visit a friend… Then I ended up staying here… My children and husband live in Nepal. My husband tells me that I should pave the way to America for our family.

I have been living here for more than a decade … I am still doing the same work … but I have changed my work many times. Work is just one aspect of my life … I am very much involved with the Nepali community and other nonprofit organizations both in the United States and Nepal. I am Nepali wherever I live, and I help the people and community however I can.

The reason these women tend to be educated professionals is because migrating to the U.S. from Nepal requires certain resources. In order to apply for a visa and purchase a plane ticket, one needs a significant amount of money. Additionally, completing the paperwork both in Nepal and the U.S. requires a certain level of literacy and education.

Though there exist these patterns among Nepali immigrants to the U.S., the Nepali immigrant experience is diverse and varied. As Dr. Shobha Gurung writes in Nepali Migrant Women: Resistance and Survival in America:

“Today, across all socioeconomic and demographic backgrounds and regions, Nepali people are migrating globally in significant numbers and for increasingly varied reasons. Some Nepalis migrate in search of economic opportunities and better livelihoods whereas others migrate to escape from the political violence, threats, and insecurity. Some people migrate for personal reasons (i.e., personal freedom and autonomy) and yet others migrate because of their transnational connections.”

It is incredibly important to acknowledge the diaspora of caste in regard to Nepali migration to the United States, as it is an issue that impacts many Nepali Americans today. Though the caste system was declared unconstitutional in Nepal in 1951, caste discrimination and bias continue to be an issue in Nepal, and these prejudices can immigrate with the higher caste Nepalis who come to the U.S.

A recent study conducted by Prem Pariyar, Bikash Gupta, and Ruvani W. Fonseka found that caste discrimination and prejudice are an issue among Nepalis in the San Francisco Bay Area. As one participant in the study described, “[T]he [caste-based] trauma I experienced earlier [in Nepal] did not leave when I arrived in the U.S.” Another said that they “have experienced discrimination in Nepal, India, the U.S., wherever there is a Nepali diaspora.” This discrimination often prevents Dalit people from engaging with the larger Nepali community.

Dalit people in the diaspora have to decide whether to live openly or conceal their identity. Though it can be helpful to avoid discrimination, the study found that constantly concealing their identities had a negative impact on the mental health of Nepali Dalit people living in the Bay Area. Others choose to live openly, as one participant in the study declared “I am proud of my caste.” Organizations such as the Nepal American Pariyar Association (NAPA), a diasporic Nepali organization for Dalit people, help build community and solidarity.

Above: a graphic from the Nepal American Pariyar Association, a diasporic Nepali organization for Dalit people.

When faced with hateful words or incidents, many Nepali Dalit people don’t know who they should turn to, due to the fact that caste isn’t a protected category in most workplaces and local government policies in the United States. Many Nepali Dalit people in the study didn’t want to register complaints with the police because caste wasn’t a protected category under the local policy, making them wonder if their complaints would just go unheard. Additionally, they worried that going to the police would cause their social standing to be lower in the diasporic Nepali community.

However, this may be changing, as including caste as a protected category is being discussed on the national level. Additionally, lawsuits regarding caste discrimination are being discussed in the courts today. For example, a Cisco employee is suing his former employer after it refused to take corrective action after he filed multiple complaints of caste discrimination with the HR department.

Many Nepalis continue to remain active in the fight to include caste as a protected category in U.S. legislation and in workplaces and universities. For example, Prem Pariyar, a Dalit activist from Chitwan, Nepal, advocated for California State University to add caste as a protected category to its nondiscrimination policy. Because of this activism, the CSU system became the first public university system to include caste as a protected category in nondiscrimination policy.

Above: Prem Pariyar, a Dalit activist from Chitwan, Nepal advocated for the CSU system to include caste as a protected category in its nondiscrimination policies.

Nepali Americans Today

Nepali Americans today are active in politics, academia, the fashion industry, and much more. Nepali organizations, both on the local and national level, continue to be important for building community. Ethnically based organizations, such as the United Sherpa Society and the Nepa Pasa Pucha Amerikya (Newar based), enable these groups to practice their specific ethnic and cultural traditions.

Even though the group is relatively small, Nepali Americans are beginning to assert themselves in politics. Harry Bhandari (Democrat) made history in 2019 when he was elected to the Maryland House of Delegates, becoming the first Nepalese American state legislator. His election was one of the most competitive in the state, as he defeated Republican incumbent Joe Cluster, former chair of the Maryland Republican Party. His priorities as a legislator include education and healthcare.

In 2022, Sarahana Shreshta (Democrat) won a New York State Assembly seat, making her the second Nepalese American state legislator and first Nepali American woman state legislator. Shreshta moved to the U.S. in 2001 from Kathmandu, becoming a citizen in 2019. According to her campaign website, she cares about advocating for working families, creating affordable housing, and fighting climate change.

Overall, many Nepalis are active in U.S. politics in different ways. From fighting back against the efforts by the Trump administration to end the temporary protected status program for immigrants impacted by disasters to advocating for the inclusion of caste as a protected category, Nepali Americans fight for what they believe in.

Additionally, as more Nepalis are immigrating to the United States, they are also bringing their food with them. Momos, a type of dumpling, is starting to become popular in the U.S. — the New York Times recently profiled a new momo restaurant in Queens and the Jackson Heights “momo crawl” challenge has blown up on TikTok. Momos can be found at food trucks and sit-down restaurants, and sometimes Indian restaurants owned by Nepali people will serve momos. If you get the chance, you should definitely try both momos and Nepali food in general!

There are many ways to engage with the Nepali American community. Look up Nepali restaurants in your area, or see if there are any events being held by Nepali American organizations that appeal to you. There are also Nepali American authors, singers, and artists whose work you can engage with. There are so many ways to interact with the community, and we hope you do!

Click on the images below to learn more about Nepali America today!